Industrial Strength Ontology Management

Aseem Das1, Wei

Wu1 & Deborah L. McGuinness2

1VerticalNet

Inc., {adas, wwu}@verticalnet.com

2Knowledge

Systems Laboratory, Stanford University, dlm@ksl.stanford.edu

Abstract

Ontologies are becoming increasingly prevalent and important in a wide range of e-commerce applications. E-commerce applications are using ontologies to support parametric searches, enhanced navigation and browsing, interoperable heterogeneous information systems, supplier enablement, configuration management, and transaction discovery. Applications such as information and service discovery and autonomous agents that are built on top of the emerging Semantic Web for the WWW also require extensive use of ontologies. Ontology-enhanced commercial applications, such as these and others require ontology management that is scalable (supporting thousands of simultaneous distributed users), available (running 365x24x7), fast, and reliable. This level of ontology management is necessary not only for the initial development and maintenance of ontologies, but is essential during deployment, when scalability, availability, reliability and performance are absolutely critical. VerticalNet’s Ontology Builder and Ontology Server products are specifically designed to provide the ontology management infrastructure needed for e-commerce applications. These tools bring the best ontology and knowledge representation practices together with the best enterprise solutions architecture to provide a robust and scalable ontology management solution.

Introduction

Ontology Builder and Ontology Server were developed in response to the business needs for ontologies in VerticalNet’s e-commerce and B2B applications. Vertical Net currently hosts 59 industry-specific e-marketplaces that span diverse industries such as manufacturing, communications, energy, and healthcare. Each e-marketplace acts as an industry-specific comprehensive resource that provides businesses and professionals with information on products, technology, industry regulations, and news and allows buyers and sellers to exchange information, source, buy, and sell products.

The primary challenge in developing these e-marketplaces is integrating the disparate sources of information in a way that presents buyers with a single, coherent browsing and navigation experience that includes contextually relevant information from all of the available sources. Suppliers have to be able to display their products on the e-marketplace in a way that enables buyers to purchase electronically, even though the suppliers maintain their product databases and availability and price information in their own vocabulary. For example, different suppliers might use the terms memory device, passives, and RAM to refer the same product and have very different internal vocabularies.

The use of standardized ontologies was seen as the best solution not only to solve these particular problems (McGuinness, 2001a and McGuinness, 2001b), but also to provide a common knowledge infrastructure for other e-commerce applications like service discovery, auctions, and request for proposal. Most of VerticalNet’s e-commerce applications are now knowledge-enabled and use standardized ontologies to drive their services.

Requirements

An extensive requirement gathering process was undertaken to compile requirements for VerticalNet’s ontology management solutions. We identified the following key requirements for ontology management for VerticalNet:

- Scalability, Availability, Reliability and Performance – These were considered essential for any ontology management solution in the commercial industrial space, both during the development and maintenance phase and the ontology deployment phase. The ontology management solution needed to allow distributed development of large-scale ontologies concurrently and collaboratively by multiple users with a high level of reliability and performance. For the deployment phase, this requirement was considered to be even more important. Applications accessing ontological data need to be up 365x24x7, support thousands of concurrent users, and be both reliable and fast.

- Ease of Use – The ontology development and maintenance process had to be simple, and the tools usable by ontologists as well as domain experts and business analysts.

- Extensible and Flexible Knowledge Representation – The knowledge model needed to incorporate the best knowledge representation practices available in the industry and be flexible and extensible enough to easily incorporate new representational features and incorporate and interoperate with different knowledge models such as RDF (Brickley-Guha, 2000) or DAML (Hendler-McGuinness, 2000).

- Distributed Multi-User Collaboration – Collaboration was seen as a key to knowledge sharing and building. Ontologists, domain experts, and business analysts need a tool that allows them to work collaboratively to create and maintain ontologies even if they work in different geographic locations.

- Security Management – The system needed to be secure to protect the integrity of the data, prevent unauthorized access, and support multiple access levels. Supporting different levels of access for different types of users would protect the integrity of data while providing an effective means of partitioning tasks and controlling changes.

- Difference and Merging – Merging facilitates knowledge reuse and sharing by enabling existing knowledge to be easily incorporated into an ontology. The ability to merge ontologies is also needed during the ontology development process to integrate versions created by different individuals into a single, consistent ontology.

- XML interfaces – Because XML is becoming widely-used for supporting interoperability and sharing information between applications, the ontology solution needed to provide XML interfaces to enable interaction and interoperability with other applications.

- Internationalization – The World Wide Web enables a global marketplace and e-commerce applications using ontological data have to serve users around the world. The ontology management solution needed to allow users to create ontologies in different languages and support the display or retrieval of ontologies using different locales based on the user’s geographical location. (For example, the transportation ontology would be displayed in Japanese, French, German, or English depending on the geographical locale of the user.)

- Versioning – Since ontologies continue to change and evolve, a versioning system for ontologies is critical. As an ontology changes over time, applications need to know what version of the ontology they are accessing and how it has changed from one version to another so that they can perform accordingly. (For example, if a supplier’s database is mapped to a particular version of an ontology and the ontology changes, the database needs to be remapped to the updated ontology, either manually or using an automated tool.)

The requirements of scalability, reliability, availability, security, internationalization and versioning were considered to be the most important for an industrial strength ontology management solution.

Existing Ontology Environments

Given the above requirements, several existing ontology management environments were evaluated:

- Ontolingua/Chimaera (Farquhar et al., 1997a,

McGuinness et al., 2000a)

- Protégé/PROMPT (Grosso et al., 1999,

Noy-Musen, 1999)

- WebOnto/Tadzebao (Domingue, 1998)

- OntoSaurus, a web browser for Loom (ISX, 1991) http://www.isi.edu/isd/ontosaurus.html)

Some of these environments have already been compared based on different criteria than those formulated at VerticalNet (Duineveld, et al., 1999). Figure 1, shows a feature set matrix and our evaluation[1] of the tools based on VerticalNet’s requirements. To keep the evaluation simple, a three level (+, 0, -) scale was used, where (+) indicates a requirement was surpassed, (0) indicates the requirement was met and (-) indicates that the tool failed to meet the requirement. Although, none of the existing ontology development environments provide all of the required features, they are nevertheless strong in particular features and have different but very expressive underlying knowledge representation models.

|

|

Scalable Available Reliable |

Ease of Use |

Knowledge Representation |

Multi User Collaboration |

Security Management |

Diff & Merge |

Internationalization |

Versioning |

|

Ontolingua/ Chimaera |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Protégé/ PROMPT |

- |

0 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

OntoWeb/ Tadzebao |

- |

0 |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

OntoSaurus/ Loom |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Figure 1: Comparison of Some Ontology Environments

Ontolingua provides a very powerful and expressive representation with its frame language and its support for KIF (Geneserth-Fikes, 1992) – a first order logic representation. In combination with its theorem prover (ATP), Ontolingua provides extensive reasoning capabilities and with Chimaera (McGuinness et al., 2000a), it supports ontology merging and diagnostics. Ontolingua also provides expressive and operational power not found in other environments such as support for generating and modifying disjoint covering partitions of classes.

WebOnto/Tadzebao provides very rich collaborative support for browsing, creating and editing ontologies, together with the ability to collaboratively annotate and hold synchronous and asynchronous ontology related discussions using the Tadzebao tool.

OntoSaurus

provides a graphical hyperlinked interface to Loom knowledge bases. Loom

provides expressive knowledge representation, automatic consistency checking

and deductive support via its deductive engine – the classifier.

Protégé is the easiest to use and supports the construction of knowledge-acquisition interfaces based on ontological data. It also has a component framework for easily integrating other components via plugins. Protégé already provides several plugins including PAL, a first order logical language for expressing constraints, and PROMPT (Noy-Musen, 1999), a tool for merging and alignment of ontologies

However, despite their strengths, all of the ontology solutions fell short on the scalability, reliability, and performance requirements, perhaps because industrial strength, commercial scalability was not seen as a important aspect of ontology management since most of the ontology usage until recently has been restricted to research and academia. Also, none of the tools provided security, internationalization, or versioning support – requirements considered critical for e-commerce applications.

After evaluating these solutions against our requirements, we decided to build our own ontology management solution with the goal of bringing the best ontology and knowledge representation practices together with the best enterprise solutions architecture to satisfy the requirements of ontology-driven e-commerce applications.

Ontology Builder

Ontology Builder is a multi-user

collaborative ontology generation and maintenance tool designed to incorporate

the best features of existing ontology toolkits in order to provide a simple,

powerful and yet broadly usable tool.

Ontology Builder uses a frame-based representation based on the OKBC

Knowledge Model (Chaudhri et al., 1997) that leverages the best of frames from

looking at the wide general acceptance of frame-based systems (Karp,

1992). Written entirely in Java,

Ontology Builder can run on multiple platforms. It is based on the J2EE (Java 2 Enterprise Edition) platform (http://java.sun.com/j2ee), which is a

standard for implementing and deploying enterprise applications. Ontology Builder also provides:

·

Import and export based on XOL (XML-based

Ontology Exchange Language) (Peter Karp et al., 1999)

·

A validation engine designed to maintain

consistency of terms stated in the language

·

A role-based security model for data security

and ontology access

· An ontological difference and merging engine

Figure 2: Ontology Builder Main Screen

Architecture

Ontology Builder is based on the J2EE (Java 2 Enterprise Edition) platform, a standard for implementing and deploying “enterprise” applications. The term “enterprise” implies highly-scalable, highly-available, highly-reliable, highly-secure, transactional, distributed applications. The J2EE technology is designed to support the rigorous demands of large-scale, distributed, mission-critical application systems and provides support for multi-tier application architecture. Multi-tier applications are typically configured to include:

- A client tier to provide the user interface

- One or more middle-tier modules that provide client services and business logic for an application

- A backend enterprise information system data tier that provides data management

The client tier is a very “thin” tier, that contains only presentation logic. The business and data logic are usually partitioned into separate components and deployed on one or more application servers. This partitioning of the application into multiple server components allows components to be easily replicated and distributed across the system, ensuring scalability, availability, reliability and performance.

Central to the J2EE platform architecture are application servers, which encapsulate the business and data logic and provide runtime support for responding to client requests, automated support for transactions, security, persistence, resource allocation, life-cycle management, and as well as lookup and other services.

Ontology Builder uses a 4-tier architecture comprised

of a presentation tier, web tier, service tier, and data tier. This architecture, shown in Figure 3, can

be deployed using a single application

server. The application server encapsulates the

service tier, which consists of the business and data logic. A single server can support many

simultaneous connections and multiple servers can be easily clustered as needed

for scalability, load balancing, and fault tolerance. Within the presentation

tier, a client can be either a Java applet or application. The clients have

easy-to-use interfaces written using the Java Swing APIs. Both applet and application-based clients

communicate with the web tier via the HTTP protocol. The

web-tier communicates with the service tier using RMI (Java Remote Method Invocation) (http://java.sun.com/products/rmi-iiop/index.html). The

service tier communicates with the data tier through the JDBC (Java Data Base

Connectivity) protocol (http://java.sun.com/products/jdbc). Collaboration is implemented using a JSDT (Java Shared Data Toolkit) server (http://java.sun.com/products/java-media/jsdt),

which forwards all

communication and change events to the respective clients.

Figure 3: The Architecture of Ontology Builder

Knowledge Representation

Ontology Builder uses

an object-oriented knowledge representation model based on and compatible with

the OKBC knowledge model and is designed to use the best practices from other

frame-based systems. The knowledge

model is similar to the Protégé-2000 knowledge model with a few differences

(Noy et al., 2000). Ontology Builder

currently supports almost all of the OKBC operations defined on classes, slots,

facets, and individuals, as well as the operations in the ask/tell interface.

Currently, however, no external interfaces are exposed to enable other

knowledge systems to use Ontology Builder as an OKBC compliant server. Interoperability, knowledge sharing, and

reuse are important goals and our future plans call for making Ontology Builder

work as a fully-compliant OKBC server.

Ontology Builder

supports a metaclass architecture to allow the introduction of flexible and

customizable behaviors into an ontology.

This could potentially be used for incorporating other knowledge models

or extending the existing knowledge model within Ontology Builder. Ontology Builder predefines certain system

constants, classes, and primitives in a default upper ontology, which can be

extended or refined to change the knowledge model and behaviors within the system. The main predefined concepts are:

- CLASS

- the default metaclass for all classes,

CLASS is an instance of itself

- SLOT – the default metaclass for all slots

and an instance of CLASS

- T – the root in the default upper ontology

(sometimes referred to as THING in other ontologies)

- INDIVIDUAL – the class of ground

objects. Operationally, every

entity that is not a class is an instance of INDIVIDUAL.[2]

- Predefined slots –

slot-minimum-cardinality, slot-maximum-cardinality, slot-value-type,

slot-value-range and domain. These

are template slots on the class SLOT.

- Predefined facets– minimum-cardinality,

maximum-cardinality, value-type, value-range and

documentation-in-frame. These

define the specific values for the slot as associated with either a class

or a slot frame.

- Predefined primitive data types – boolean,

string, integer, float, date, etc.

An ontology is

composed of classes, slots, individuals and facets,

which are all implemented as frames. Ontology

itself is also defined as a frame and contains information such as author, date

created and documentation. Both classes

and slots support multiple-inheritance in an Ontology Builder ontology.

Classes are all instances of the metaclass CLASS by

default, which is changeable by the user.

Classes can be instances of multiple metaclasses and they may be

subclasses of multiple superclasses.

Slots are defined independently of any class and are

instances of the metaclass SLOT by default, which is also changeable by the

user. They can also be instances of

multiple metaclasses and parent classes.

Like classes, slots also support a multiple-inheritance hierarchy. Slot hierarchies can be used to model

naturally hierarchical relationships between terms. For example, you might need to model the notion of price along

with the subrelations of wholesale-price, retail-price, and

discount-price.

Slots can be attached

to a class frame or a slot frame, as slots are themselves first-class objects

and when attached describe the properties of the frame. A slot can be attached either as a template

slot or as an own slot. Own

slots cannot be directly attached to a frame, but are acquired by the frame

(class, slot or individual) being an instance of another class. Template slots can be directly attached to

either a class or a slot frame. The

domain own slot (acquired by a slot frame from being an instance of class SLOT)

is useful for limiting the applicability of the slot only to the specified

domain class and its subclasses. If a

slot does not define a domain, it can be applied to all classes in an

ontology. This flexibility is often

useful during the early stage of ontology development when the slots used in an

ontology are still being refined. Later

however, it is often useful to define a domain for slots so that they are only

used in specific contexts.

Facets specify the specific values for a slot-class

or a slot-slot association. A facet is

considered associated with a frame-slot pair, if the facet has a value for that

association. The predefined facets

(value-type, value-range, minimum-cardinality, maximum-cardinality etc.) hold

the values given to a slot’s own slots (slot-value-type, slot-value-range,

etc.) when the slot is associated with a frame. The facet values can only be a specialization of the slot frame’s

own slot values. For example, if slot color

is defined to have a slot-value-type of “color”, when it’s attached to a frame,

the value can only be changed to a specialization of “color”, “rgbcolor” or

“hsvcolor”. If the value is changed,

then the “value-type” facet will hold the changed value. In addition to predefined facets, Ontology

Builder supports the creation and use of user-defined facets. A user-defined facet can be created and

attached to a slot when the slot is attached to a frame. For example, a user-defined facet might be

used to specify whether or not a slot is “displayable”.

Ontology Inclusion (Uses Relationship)

Ontology construction is time consuming and expensive. To lower development and maintenance cost, it is beneficial to build reusable and modular ontologies so that new ontologies can be created and assembled quickly by mixing and matching existing validated ontologies. Both Ontolingua and Protégé have the capability to include ontologies for the purpose of reuse (Farquhar et al., 1997b, Protégé 2000). Protégé allows projects to be included, but the included projects cannot be easily removed and no duplicated names can exist across projects used (included projects plus the current working project) due to the requirement that names must be unique. This unique name requirement in Protégé is limiting because duplicate names occur in practice. Ontolingua provides facilities that allow flexible combination of axioms and definitions of multiple ontologies. Ontolingua eliminates symbol conflicts among ontologies in its internal representation by providing a local name space for symbols defined in each ontology.

Ontology Builder supports concepts reuse and ontology inclusion through the “uses” relationship. The “uses” relationship allows all classes, instances, slots, and facets from the included ontology to be visible and used by an ontology. For example, if ontology A “uses” ontology B, all of the concepts defined in ontology B (classes, instances, slots and facets) can be referenced from ontology A. A class in ontology A can be a subclass of a class in ontology B, and any class in A can use any slots defined in ontology B. The “uses” relationship can be added or removed easily from an ontology. When a “uses” relationship is removed, inconsistencies might exist in the current working ontology because concepts defined in the removed “uses” ontology still are being referenced, even though the ontology is not being used. Changes made to an ontology are propagated in real-time to all ontologies that use that ontology. Although this ensures that the latest concepts are available for use, it might also cause inconsistencies. Validation can be performed to diagnose and identify frames that have inconsistencies

The “uses” relationship is transitive. If ontology A “uses” ontology B, and ontology B “uses” ontology C, then ontology A “uses” ontology C automatically. Ontology Builder also allows cyclical “uses” relationship, that is ontologies A and B can both use each other. Concepts are unambiguously identified by using a globally unique identifier that is generated automatically when a concept is first created; or by using a fully qualified name. A fully qualified name is the concept name concatenated together with the “@” and the ontology name. For example, car@transportation. The fully qualified name is guaranteed to be unique as a concept name is enforced to be to be unique within a specific ontology and ontology names are unique across all ontologies in the knowledge base. The fully qualified names are used automatically when working with concepts in ontologies other than the ontology where they are initially defined.

Data Storage and Knowledge-Relational

Mapping

Knowledge-base systems

traditionally used the computer’s main memory for storing the knowledge needed

at run-time. The amount of information

that can be stored is limited by the available memory and there might be an

initial delay in loading all of the entities into memory from a flat file. Moreover, the storing of the knowledge model

in flat files is not secure, is error-prone, and quickly becomes unmanageable

as the size of the knowledge base increases. Object-Oriented Database Systems

(OODS) can also be used to store the knowledge model and provide superior

modeling for representing the relations and hierarchies within an

ontology. However, when compared to

relational DBMS (RDBMS), OODS lack in performance, enterprise usage and acceptance,

internationalization support, and other features. RDBMS are still the storage mechanism of choice in enterprise

computing when it comes to storing large amounts of performance-critical

data. RDBMS can store gigabytes of data,

search several million rows of data extremely quickly, and also support data

replication and redundancy.

Ontology Builder uses

an enterprise-class RDBMS so that very large-scale ontologies and large numbers

of ontologies can be stored and retrieved quickly and efficiently. Several other knowledge based systems SOPHIA

(Abernethy-Altman, 1998) and an environment for large ontologies motivated by

PARKA (Stoffel et al., 1977) have also used RDBMS for these and other similar

reasons. Ontology Builder currently supports

the Oracle 8 and Microsoft SQL Server RDBMSs for data storage.

Ontology Builder

employs a sophisticated database schema to represent the OKBC based knowledge

model and can support all OKBC-defined operations that could be performed on

classes, instances, slots and facets, as well as the operations specified by the

OKBC ask/tell interface. The multiple-table database schema also supports

internationalization, which permits ontologies to be developed in any

language. Multiple translations of the

same ontology can coexist in the same database and can be used to view the same

ontology in different locales. The

schema is normalized; each piece of information is stored in only one location

so that modifications to a concept are automatically propagated to all entities

that use that concept.

Knowledge-relational

mapping is accomplished via a high-performance persistence layer that converts

relational data to and from in-memory Java objects that represent the different

entities and relationships of the knowledge model. Information retrieval is optimized to retrieve information about

multiple concepts via one JDBC database call, which dramatically improves performance. Moreover, a lazy-loading algorithm is used

to retrieve information on an as-need basis.

For example, when an ontology is first loaded, only the classes and the

class hierarchy are loaded; attached slots, slot values, and facet values are

only loaded when a user decides to browse or edit a particular class.

Multi User Collaboration & Locking

Ontology construction

is often a collaborative endeavor where the participants in the ontology

building process share their knowledge to come to a common understanding and

representation of the ontology. These

participants might be geographically separated and for collaboration require

the ability to hold discussions and view the changes made to the ontology by

other collaborators. Ontology Builder

provides this type of multi-user collaborative

environment. Collaborators can hold

discussions individually or in a group and see changes made to the ontology by

other collaborators in real time.

Collaboration is

implemented via the Java Data Shared Toolkit (JSDT), which provides the

communication, messaging, and session management infrastructure for

collaboration within Ontology Builder.

As they log into the system, each user is registered with the JSDT

server in a default “global” discussion room.

Messages sent by any user in this discussion room are received by all

other current users of the system. Each

ontology also defines its own discussion room, which is created the first time

any user opens the ontology for browsing or editing. Users who open the same ontology are added to that ontology’s

discussion room automatically and can see the messages from and collaborate

with other users within that ontology’s discussion room. A user can also open a private chat session

with any other user who is logged on to the system.

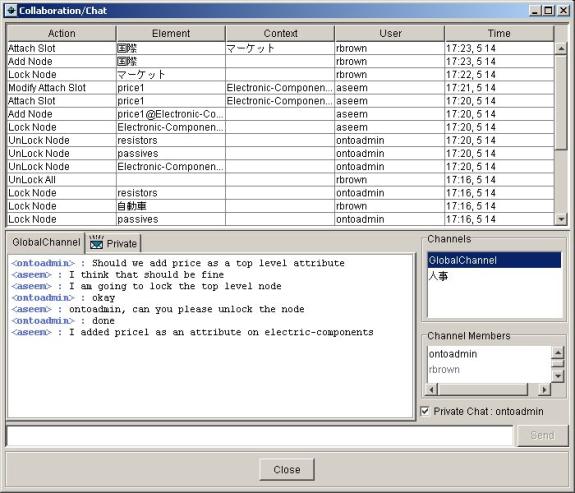

Edits to any ontology

in the system are broadcasted to all users, regardless of their interest. The change record indicates the type of edit

operation, the affected concept and ontology, and the user who performed the

action. Figure 4 is a snapshot of the

collaboration window that shows the system log and a discussion between

collaborators. Any changes to the

ontology are committed to the database immediately, so that the changes are

available to all other users in real time. An icon is displayed automatically

next to the concepts within an open ontology that have been modified by other

users, indicating to the user that the information currently displayed in the

Ontology Builder client is no longer accurate.

The user might already know what has changed based on the discussion

with other collaborators or can look in the system messages to see exactly what

was changed in the affected concept. An

ontology can be refreshed at any point to retrieve the latest state.

Since multiple

collaborators can make changes to the same ontology, some kind of locking

scheme is necessary to prevent users from overwriting each other’s changes. Ontology Builder uses a pessimistic locking

strategy that requires an explicit lock to be acquired by a collaborator before

any edits are allowed to a concept.

Explicitly locking a concept implicitly locks all of the parents and

children of the locked concept, preventing other users from editing either the

children or the parents of the locked node. Explicitly locking a concept still

allows other users to edit the siblings of the locked concept. Locked concepts are shown with a locked icon

in all of the clients, indicating which concepts are currently being

edited. This locking strategy enables

multi-user collaboration and reduces inconsistencies generated from multiple collaborators

working on the same ontology.

Figure 4: Collaboration Window in Ontology Builder

Validation

Ontology Builder

provides a validation engine to resolve any inconsistencies that might have

been introduced during the ontology development and maintenance process. Maintaining consistency is not only critical

during the development process where a particular ontology might “use” other

ontologies, it is absolutely critical during the deployment phase where the

ontologies have to be valid and consistent so that they can be used by

applications consistently without any errors.

Real-time validation is a fairly complex task and requires a truth

maintenance system (TMS) of some sort in order to have acceptable performance.

If a TMS is not used, thorough checks of all of the elements of the ontology

need to be done, which is not acceptable from a performance perspective. Ontology Builder does some real-time

validation during the edit/creation process itself (for example, it checks for

value-type and cardinality violations), but for a full consistency check, the

validation engine needs to be explicitly invoked by the user. The validation engine checks for:

- Cycles

- Domain of slots is valid for the classes

to which they are attached

- Minimum cardinality <= maximum

cardinality

- Minimum cardinality <= num of values

<= maximum cardinality

- Values are of specified value-types

- Undefined symbols – symbols that are being

used but not defined in the current ontology or any of the ontologies it

uses

- Attached slots are consistent with the

slot definition (Specialization of value-types, value-ranges and cardinalities

is checked for consistency)

Difference & Merging

Merging ontologies becomes necessary when there is a need to consolidate concepts defined in multiple ontologies, often developed by different teams or gathered from various sources, into a consistent and unified ontology that can be deployed with e-commerce applications. Because the general task of merging ontologies can become arbitrarily difficult, extensive human intervention and negotiation are required. Chimaera (McGuinness et al., 2000b) and PROMPT (Noy-Musen, 2000) provide semi-automated tools to facilitate the merging process. The merging tools in Chimaera and PROMPT suggest a list of merging candidates and present available operations on the candidate frames. Once a user finishes a particular merge operation, more suggestions could be generated and the tool guides the users to finish the merging process. Chimaera also provides diagnostics on the results of merging and other ontology modifications.

Ontology Builder follows a different path in that the initial list of merging candidate frames is not generated. Instead, Ontology Builder relies on the user to decide where to start the merging process. Essentially the user determines when two concepts mean the same thing semantically. The rationale behind the decision is that in practice a user often knows the structures and contents of the ontologies to be merged, and thus has the knowledge to determine where to start the merging process. The goal of the difference and merge service in Ontology Builder is to speed up the merge process once the initial merging candidate frames have been chosen, rather than being a general-purpose merging tool like those provided by Chimaera and PROMPT.

In Ontology Builder,

the merge operation does not generate a third ontology that contains the merged

results from two input ontologies. Instead,

Ontology Builder defines a base ontology and merge ontology where the

differences between the two ontologies can be initially identified and then, if

desired, the differences can be merged into the base ontology.

Ontology Builder currently has a simplistic algorithm for reporting the differences between two ontologies. Differences are reported for the two concepts selected for comparison as well as for their children that have matching names. If there are no matching names, the differencing stops. Ontology Builder reports the following differences:

- Missing children/parents

- Missing slots

- Value, value-type, value-range, domain, documentation, and cardinality differences for matched concepts

If desired, the differences can be merged. The merge operation

- Copies missing children recursively to the base ontology

- Copies

missing slots to the base ontology

- Merges

documentation, slot values, value-types, value-ranges and cardinalities

for the matched concepts

The difference and

merge feature of Ontology Builder is simple compared to the merging features

available in other tools like PROMPT or Chimaera, but future plans call for

enhancing this functionality based on further requirements and proposed usage.

Role Based Security

Ontology Builder

provides a flexible security model designed to allow client access to the

back-end services. Every user has an

account on the system and is only allowed to access the back-end services if

properly authenticated. Each user is

assigned a role, which denotes the level of access for ontology

management. Users assigned a particular

role can only perform the operations allowed by that role, however, users can

be assigned different roles for different ontologies. The security model also enables a much finer-grained permissions

system where individual edit operations in an ontology (such as

modify-documentation) can be enabled for particular users.

By protecting ontology

data and controlling access to back-end services, Ontology Builder’s security

model meets one of the critical requirements for enterprise class applications.

Internationalization

Ontology Builder is

fully internationalized and can support the browsing and editing of ontologies

in multiple locales. A single

representation of the ontology is maintained for all locales. Names from each

of the locales are linked to this one representation so that changes in

ontology structure in one locale are propagated and available in all the other

locales. Concepts, which have not been

translated in a particular locale, are shown in the locale in which they were

initially created. For example, if the

ontology was initially created in English and then partially translated into

Japanese, browsing it in Japanese will show the names in English for the

concepts that have not yet been translated.

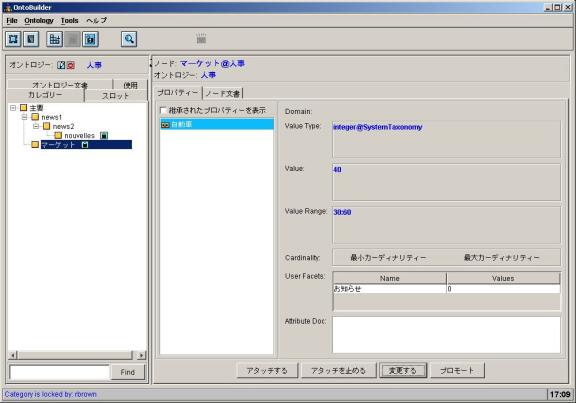

Ontology Builder also provides support for translating from one locale

into another locale. The snapshot in

Figure 5 shows a Japanese ontology with some untranslated words in English and

French.

Figure 5: Ontology creation in Japanese

Import & Export

Ontology

Builder provides import and export functionality based on XOL (XML based

Ontology Exchange Language) (Karp, et al. 2000). XOL is based on OKBC-Lite, a simplified form of the OKBC

knowledge model, and is “designed

to provide a mechanism for encoding ontologies within a flat file that may be

easily published on the WWW for exchange among a set of application

developers.” The XOL DTD used by

Ontology Builder has been modified to support internationalization, metaclass,

uses, and facet definitions, which are not part of the original DTD.

Ontology Server

Ontology Server is a scalable, high-performance server and is a critical component for e-commerce applications that require ontologies to drive their services. It provides a very scalable, available, reliable, and high-performance solution. Ontology Server uses exactly the same architecture and representation as Ontology Builder and provides XML and Java RMI interfaces for access to the ontological data. It is optimized for read-only access, which facilitates the use of data-caching mechanisms to enhance performance, which is critical for e-commerce applications. Ontology Server defines its own interfaces, which are simpler and more suitable for e-commerce applications than the general OKBC interface.

Usage & Performance

Ontology Builder was released internally for use by VerticalNet ontologists and domain experts in April 2000, following a beta release in Feb 2000. The server - a Sun Ultra 1/60, 1 Gigabytes of RAM, with Oracle 8.0.4 - is hosted out of Palo Alto and accessed mainly from Horsham, Pennsylvania but it is also accessed from several other locations. Over the past year 84 different users have created 974 ontologies on the server. Concurrent usage peaked at about 20 users using the system at one time. The current database has over 5 million records, consisting of 650,000 classes, 480,000 slots, 680,000 frame-slot relations, 220,000 frame-slot-facet relations, 650,000 parent-child relations and 1,100,000 meta-class relations.

Ontology Builder and Ontology Server both use the same

architecture and back-end services.

However, Ontology Server is optimized for read-only access to the

ontological data and gives better performance than Ontology Builder for read

operations. Figure 6, shows the

performance graph for read operations for Ontology Server. 32, 64, 128, 256, 512 and 1024 clients were

simulated accessing 128 different frames, each frame being accessed by each

client 100 times. The performance tests

were done on a Windows 2000 Pentium III (800 mHz) machine with 512 megabytes of

RAM, using SQLServer 2000 default configuration without any tuning. Multiple clients were simulated using

multiple threads on a Windows 2000 Pentium

III (800 mHz) machine. The performance

data is given for average response time - the time experienced by a

client to retrieve a frame, including server processing time, networking delay,

lookup and Java serialization/deserialization and for transactions per

second – the number of frame accesses per second.

Figure 6: Performance graph for

Ontology Server

The graph shows that the maximum throughput (transactions per second) is achieved when the number of clients is the same as the number of frames being accessed. If the number of clients is fewer than the number of available frames then the server is not being fully utilized (shown on the graph for 32 and 64 users). As the number of clients increases, the throughput remains almost the same but the average response time increases, as now clients have to wait for previous requests from other clients to complete.

Excluding the networking, serialization and lookup time, Ontology Server’s actual processing time

is only 3-5 milliseconds and does not vary significantly with the number of

clients, once the frame has been initially loaded from the database. The initial loading time is about 10–1000

milliseconds for each frame, depending on the number of slots, facets, class,

parents, children and metaclass relations to be retrieved. Once retrieved, the application server

caches the frame and subsequent requests to retrieve that frame take only

3-5milliseconds regardless of the client requesting the frame. The number of frames to be cached can be

specified as a parameter. Frames not

being accessed for a while are cached out and replaced with the newly requested

frames as the caching limit is reached.

A server response time of 3-5 milliseconds means that the same or

multiple clients can access a single frame 200 times per second. The throughput dramatically increases if

multiple frames are being served for multiple clients. If 100 different frames are accessed, with

the response time of 5 milliseconds per frame after the initial load time, then

the throughput is 100 * 200 = 20,000 frame accesses per second. As noted above, multiple servers can be

clustered to allow connections from thousands of users. Since, all of our tables use primary keys,

the size of the database and tables does not significantly increase the initial

loading time of the frame. Figure 7,

shows the access time in milliseconds for retrieving a bare frame (with no

relational information) from the frame table with different sizes.

|

Num. Of Rows |

Min. Time |

Max. Time |

Avg. Time |

Iterations |

|

1000 |

3.12 |

14.45 |

7.2 |

200 |

|

10,000 |

3.84 |

17.12 |

7.75 |

200 |

|

100,000 |

3.23 |

15.78 |

9.35 |

200 |

|

1,000,000 |

4.52 |

19.35 |

11.85 |

200 |

Figure 7: Access time for retrieving from database

table with different sizes

Ontology Builder does not use caching for retrieving ontological data, but uses lazy loading to retrieve information as needed. Each piece of information is retrieved from the database every time it is requested. For the same machine configuration as described above, the actual processing time to retrieve a simple frame with parents, children, metaclasses and slots (without slot values and frame-slot-facets) is about 35 milliseconds, which translates into 30 frame accesses per second. The average time to create a simple frame in Ontology Builder is about 20 milliseconds, which translates into 50 write transactions per second. In practice this level of performance for Ontology Builder has proved to be acceptable, as the ontology development and maintenance is not a performance intensive process. Clustering multiple servers and tuning the database can further improve Ontology Builder’s performance.

Discussion

Ontologies are

becoming much more common as a core component of e-commerce applications. Industrial strength solutions are needed

and, in fact, critical for the success and longevity of these

applications. We have presented two

Vertical Net products: Ontology Builder

and Ontology Server. We believe these

products bring together the best knowledge management and ontology practices

and the best enterprise architectures to provide industrial-strength solutions

for ontology creation, maintenance, and deployment.

When evaluated against

our initial product requirements, Ontology Builder and Ontology Server meet or

surpass most of the requirements.

Figure 8, shows this evaluation and compares Ontology Builder with the

ontology environments compared in Figure 1.

Even though we have provided reasonable solutions to most requirements,

designated by a 0, we believe there is still considerable room for improvement

and plan to continue to enhance functionality in these particular areas.

|

|

Scalable Available Reliable |

Ease of Use |

Knowledge Representation |

Multi User Collaboration |

Security |

Diff & Merge |

Internationalization |

Versioning |

|

Ontolingua/ Chimaera |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

Protégé/ PROMPT |

- |

0 |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

|

OntoWeb Tadzebao |

- |

0 |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

OntoSaurus/ Loom |

- |

- |

+ |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Ontology Builder |

+ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

+ |

- |

Figure 8: Comparison of Ontology Builder with other Ontology Environments

We believe we have

delivered a robust solution for our most critical requirements –scalability,

availability, reliability and performance.

By using an enterprise architecture (J2EE) and an enterprise RDBMS as

the back end storage, we have provided an enterprise-class scalable, reliable,

available, and high-performance ontology management solution.

The Ontology Builder

client provides an easy-to-use interface for ontologists, domain experts, and

business analysts. However, we believe,

there is always room for improvement in user-interface design and usability and

plan additional work on usability.

Our knowledge model is

based on the OKBC knowledge model and provides flexibility and extensibility

for incorporating new features and existing knowledge models. However, Ontology Builder does not support

axioms yet and does not include a full reasoning component. While we do support internal consistency

checking and propagation of implicit information, we do not provide an OKBC

interface and thus do not support full OKBC compliance. We plan to extend our knowledge model to

support axiomatic reasoning and also plan to implement an OKBC interface. Our current import/export format is XOL,

future plans include support for other common formats such as RDF and DAML+OIL.

We have provided a multi-user collaborative environment to facilitate the ontology building, sharing, and maintenance process. Collaborators can hold discussions and see changes committed by other users. The collaborative environment could be further improved by providing optimistic locking (where a frame is not allowed to be edited, only when it is being updated) instead of pessimistic locking. We are also investigating a more complete conferencing and whiteboarding solution, perhaps by integrating a third party tool like Microsoft NetMeeting (http://www.microsoft.com/windows/netmeeting/default.asp) or Netscape Conference (http://home.netscape.com/communicator/conference/v4.0).

Our role-based security model provides data security, data integrity, user authentication and multiple levels of user access. A fine-grained model in which a set of permissions could be assigned to a user of a particular ontology has also been designed.

The difference and merging engine currently uses a simple algorithm. Future plans call for a more sophisticated difference and merging algorithm

Ontology Builder is fully internationalized and can be used in multiple languages and ontologies can be created and displayed in multiple locales.

Ontology Builder currently does not provide any versioning support. Versioning of ontologies is needed so that changes from one version to another can be tracked and managed and so that applications can determine what specific version of an ontology is being accessed. We hope to provide fine-grain versioning control functionality in the future.

Acknowledgements

We like to thank the

many people who have contributed to these products - Mark Yang for his

contributions on design and development, Howard Liu, Don McKay, Keith Thurston,

Lisa Colvin, Patrick Cassidy, Mike Malloy, Leo Orbst, Eric Elias, Craig

Schlenoff and Eric Peterson for their use and valuable feedback, Joel Nava,

Faisal Aslam, Hammad Sophie, Doug Cheseney and Nigel McKay for implementation

and Hugo Daley and Adam Cheyer for their support.

References

Neil F. Abernethy,

Russ B. Altman, “SOPHIA: Providing basic knowledge services with a common DBMS”,

Proceedings of the 5th KRDB Workshop, Seattle, WA, 1998.

Dan Brickley & R.V.Guha, "Resource Description Framework (RDF) Schema Specification 1.0", World Wide Web Consortium, Cambridge, MA, 1999

Vinay

Chaudhri, Adam Farquhar, Richard Fikes, Peter Karp, James Rice, “Open Knowledge

Base Connectivity 2.0”, Knowledge Systems Laboratory, 1998.

J.

Domingue, “Tadzebao and WebOnto: Discussing, Browsing, and Editing Ontologies

on theWeb”, Proceedings of the Eleventh Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition,

Modeling and Management, Banff, Canada, 1998.

A. J.

Duineveld, R. Stoter, M. R. Weiden, B. Kenepa & V. R. Benjamins, “WonderTools?

A

comparative study of ontological engineering tools”, Proceedings of the

Twelfth Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition, Modeling and Management, Banff, Canada, 1999.

Adam Farquhar, Richard

Fikes, James Rice, “The Ontolingua Server: a Tool for Collaboartive Ontology

Construction”, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 46,

707-727, 1997

Adam Farquhar, Richard

Fikes, James Rice, “Tools for assembling modular ontologies in Ontolingua”, Knowledge

Systems Laboratory, Stanford University, April, 1997

Michael Genesereth and

Richard Fikes, “Knowledge Interchange Format, Version 3.0 Reference Manual”,

Knowledge System Laboratory, Stanford University, 1992.

W. E. Grosso, H. Eriksson, R. W. Fergerson, J. H. Gennari, S. W. Tu, & M. A. Musen, “Knowledge Modeling at the Millennium (The Design and Evolution of Protege-2000)”. Twelfth Banff Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition, Modeling, and Management. Banff, Alberta, 1999.

James Hendler and Deborah L. McGuinness, ``The DARPA Agent Markup Language''. IEEE Intelligent Systems, Vol. 15, No. 6, November/December 2000, pages 67-73.

ISX Corporation (1991). "LOOM Users Guide, Version

1.4".

Peter D. Karp, "The design space of frame knowledge representation systems", Technical Report 520, SRI International AI Center, 1992.

P.

D. Karp, V. K. Chaudhri, and J. F. Thomere, "XOL: An XML-Based Ontology

Exchange Language," Technical Note 559, AI Center, SRI International,

1999.

Deborah L. McGuinness, Richard Fikes, James Rice, and Steve Wilder, “An Environment for Merging and Testing Large Ontologies. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning, Breckenridge, Colorado, 2000.

Deborah L. McGuinness, Richard Fikes, James Rice, and Steve Wilder, “The Chimaera Ontology Environment”, Proceedings of the The Seventeenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, Texas, 2000.

Deborah L. McGuinness ``Ontologies and Online Commerce''. In IEEE Intelligent Systems, Vol. 16, No. 1, January/February 2001, pages 8-14.

Deborah L. McGuinness. “Ontologies Come of Age”. To appear in D. Fensel, J. Hendler, H. Lieberman, and W. Wahlster (editors). Semantic Web Technology, MIT Press, Boston, Mass., 2001.

N. F.

Noy & M. A. Musen, “SMART: Automated Support for Ontology Merging and

Alignment”, Proceedings of the Twelfth Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition, Modeling

and Management, Banff, Canada,

1999.

N. F. Noy & M. A. Musen, “PROMPT: Algorithm and Tool for Automated Ontology Merging and Alignment”, Seventeenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Austin, Texas, 2000.

N. F. Noy, R. W. Fergerson, & M. A. Musen, “The knowledge model of Protege-2000: Combining interoperability and flexibility”, Second International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management, Juan-les-Pins, France, 2000.

Protégé Users Guide, http://www.smi.stanford.edu/projects/protege/doc/users_guide/index.html

Kilian Stoffel, Merwyn Taylor, James Hendler, “Efficient

Management of Very Large Ontologies”, Proceedings of American Association for

Artificial Intelligence Conference, (AAAI-97), AAAI/MIT Press 1997.